When fans blow in the science classrooms at Lincoln R-2 middle school, sometimes they help seventh graders produce wind energy with demonstration kits developed for classroom courses supported by electric cooperatives.

“They’re able to change fin sizes and pitch to capture more energy and send it down the line,” says Becky Mueller, who teaches junior high science in Lincoln, Missouri. “The kids ‘get it’ a lot better when they can see and touch things. It really makes a huge difference.”

Mueller is one of more than 90 classroom teachers who’ve completed the Energy in Today’s Classroom Program developed by Jefferson City-based Central Electric Power Cooperative with help from the University of Missouri-Columbia Agricultural Systems Management Department.

The two-day graduate level course is designed to fully support Missouri’s statewide educational standards, and has been refined as classroom materials have changed.

“I’m more confident about being able to say ‘this is how it works’ than I was before I took the course,” says Mueller, who took the course in 2013. “I can explain why turbines are important and why step up and step down transformers are important for safety.”

Mueller can confidently explain how electric cooperatives operate differently than investor-owned utilities.

“Members own electric co-ops, so they want prices to stay low, but companies own [IOUs] and they are interested in profit, so prices can be higher.”

Course elements includ: energy basics; generation and transmission; energy efficiency; energy sources; economics and energy production; and a tour of the power plants serving the University of Missouri system.

“Our goal is to provide useful and objective information on energy to teachers that they can use to support educational requirements students face throughout the year,” said Nancy Gibler, director of business development for CEPC.

The G&T initially offered the course for teachers working within its service territory, but has since extended the offers to even more educators in the region.

“So teachers not only come from Missouri, but also from northeastern Oklahoma, and southeastern Iowa,” she said.

Feedback from course participants has been overwhelmingly positive.

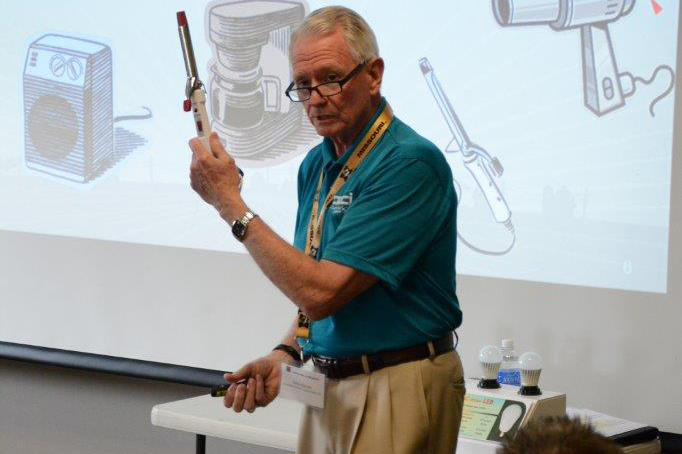

“Classroom value for the teachers helps really sell the course,” sais Mark Newbold, CEPC’s drector of administrative services. “Teachers leave with materials and demonstration supplies that they can use back in their classroom.”

They also leave with one graduate credit hour for continuing education and 15 hours of credit for state-mandated professional development training that teachers are expected to complete annually.

“The course gave me tons of background knowledge on electricity,” says Sarah Gurney, a seventh grade science teacher for Willard Middle School, in Willard, Mo., who attended the sessions in 2015.

“Children need real life examples, and being able to explain how the polls, wires, transformers and other equipment helps power all the devices plugged into their home outlets makes learning easier.” Gurney says. “When you can make concepts more concrete and then move into the abstract, you get better academic results.”

The impact reaches deep into the territories of the region’s electric cooperatives, providing meaningful learning experiences for students from elementary through high school.

“Most of these teachers are seeing at least 100 students per day, so we’re slowly but surely making a difference in what tomorrow’s future co-op consumer-members know about energy,” said CEPC’s Keith Mueller. “They include science teachers, vocational agriculture teachers and even a music teacher who developed an after school program for students that’s focused on energy.”

Each fall, Mueller and other CEPC representatives meet with staff from the University of Missouri-Columbia Agricultural Systems Management Department to discuss changes to the course and ways to make the experiences for teachers more meaningful.

“We’re considering including more information on solar in our renewable energy discussions because interest in the technology is so high,” said Mueller. “The real beauty of the course as its designed is that we can work directly with the university to make changes based upon the feedback we get each year from participants.”

Derrill Holly is a staff writer at NRECA.